Berlin

Day 1 - Mitte

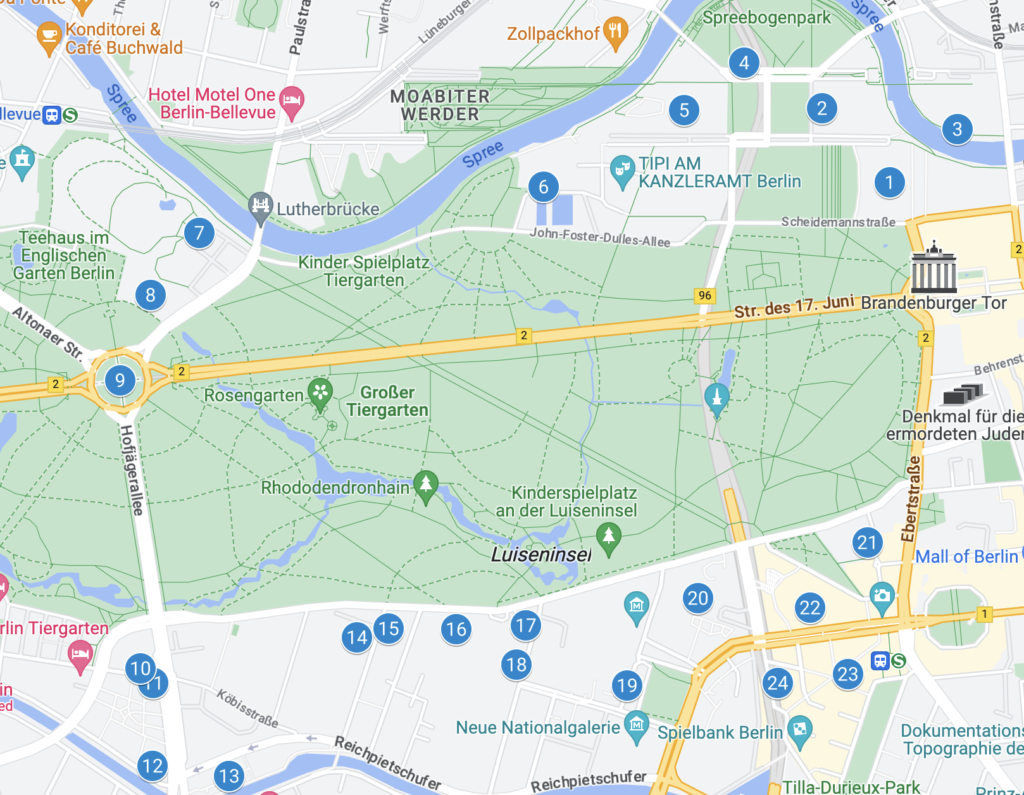

Berlin is an ideal city for those who love walking because, despite its considerable size, it is compact and divided into well-defined neighborhoods, each with its own points of interest and attractions easily reachable on foot. “Day 1- Mitte” is a perfect walk if you are visiting the city for the first time, as it covers the main monuments and famous places in the capital. To understand how the urban landscape has changed since reunification, follow the “Day 2 – Contemporary Architecture” itinerary. Enjoy your walks!

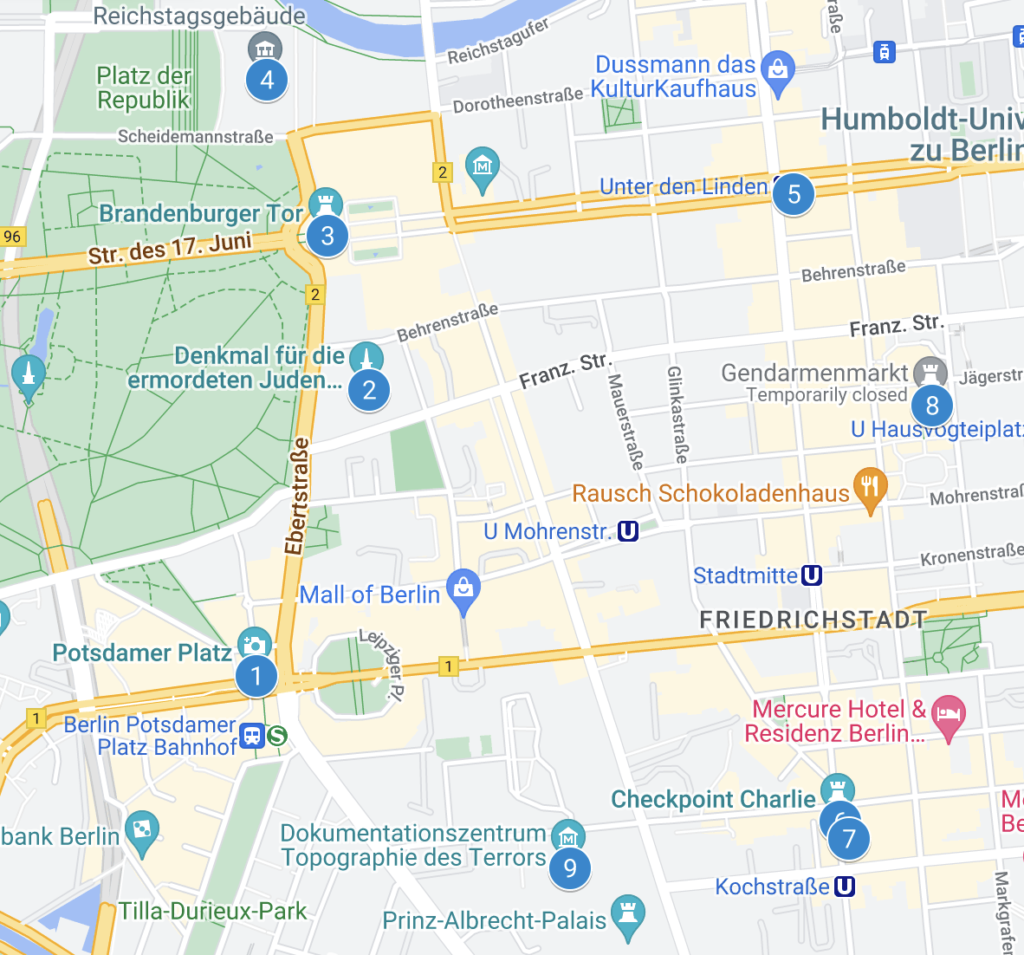

This itinerary, which requires a full day, covers all the classic monuments of Berlin and some fabulous spots in the city that are less known. Along the way, you will see picturesque views, impressive architecture, inviting local eateries to grab a bite, and numerous places you probably know from history books. The itinerary starts from Potsdamer Platz and winds through the new ministerial quarter, reaches Unter den Linden, and then continues through the historic center, ending in Scheunenviertel.

So, start from Potsdamer Platz, the newest area of Berlin, a true showcase of contemporary architecture. Storefront of urban renewal, Potsdamer Platz is perhaps the most visible symbol of the “new Berlin” and a major tourist attraction. This historic square was once a bustling crossroads that became synonymous with metropolitan life and entertainment in the early 20th century. In 1924, Europe’s first traffic light (which operated manually) was installed here, a copy of which has recently been placed in its original location. World War II drained all life from Potsdamer Platz, and the entire area was frozen, cut in two by the Wall, until reunification. In the 1990s, the city administration engaged the best international talents in contemporary architecture, including Arata Isozaki, Rafael Moneo, Richard Rogers, and Helmut Jahn, to realize ‘Potsdamer Platz – Part Two’ as part of architect Renzo Piano’s overall project. Constrained by the city’s zoning regulations, the final result cannot be described as avant-garde, but it is pleasant and, above all, human-scale.

Berliners and visitors have warmly embraced this new urban development, which is divided into three parts: DaimlerCity, the Sony Center, and the Beisheim Center. DaimlerCity, which extends south of Potsdamer Strasse, was the first project to be completed in 1998. The Sony Center, nestled between Potsdamer Strasse, Ben-Gurion-Strasse, and Bellevuestrasse, was inaugurated in 2000. The last of the three projects, the Beisheim Center, is the most recent, opened in 2004, and occupies the triangle formed by Lenné-, Bellevue-, and Ebertstrasse. If you want to get a bird’s-eye view of the area, you can take what is considered the ‘fastest elevator in the world’ at Panorama Punkt

Take a look at the stretches of the Berlin Wall. The word “wall” does not describe the full extent of the barrier which cut Berlin into two halves from 1961 to 1989. The Berlin Wall was, in fact, a wide corridor between two walls. One wall marked the actual border on the west side of the corridor, while a second wall closed off the corridor to the east. The death strip, which included a narrow sentry path for the border guards of the GDR, lay in between. In the inner city, the corridor separated the old city centre along its northern, western and southern boundaries from the West-Berlin districts of Wedding, Tier-garten and Kreuzberg. Today a twin row of cobble-stones stretching several kilometres marks the exact location of the former border wall, and is being gradually extended. The Wall that encircled West-Berlin for almost thirty years had a total length of 160 kilometres. Of these, 45 kilometres separated the west from the east part of the city, while a stretch of 115 kilometres cut it off completely from the neighbouring Land of Brandenburg. More than 100 sites commemorating the victims and particular Wall-related incidents are spread along this route today. In 2001, the Berlin Senate launched its “Berlin Wall Trail” project with the aim of gradually making the entire 160 kilometers of the former Wall accessible to pedestrians and cyclists. Signs indicate the direction, aerial views afford an overall perspective, and information points highlight historically significant sites, thereby complementing the information boards installed by the Geschichtsmeile Berliner Mauer (Berlin Wall History Mile) initiative.

Continue north along Ebertstrasse to the Holocaust Mahnmal 5 (p83), the memorial for the victims of the Holocaust, a visually and emotionally impactful work, especially if you take the time to wander among the tall concrete blocks, appreciating their expressive power.

It took 17 years of discussions, planning, and construction, but finally, on May 8, 2005, the Monument to the Jewish victims of the Nazi genocide during the Second World War was inaugurated. Generally known as the Holocaust Memorial, it occupies a space comparable to a soccer field immediately south of the Brandenburg Gate. The New York architect Peter Eisenmann conceived a vast grid of 2,711 rectangular concrete blocks of varying heights placed on undulating terrain, resembling a kind of giant cemetery. Visitors have unrestricted access to this labyrinth from any point and can move independently.

At first glance, the monument may appear sober and emotionally detached, but give yourself time to appreciate the complexity of the project, to experience the coldness of the stone structures, and to observe the play of light and shadow. To learn more about the tragic historical period to which the monument refers, visit the underground Information Center (Ort der Information), whose entrance is on the eastern side. The timeline graph of the persecution of Jews during the Third Reich is followed by rooms that document the personal history of some victims and entire families through documents.

In a darkened room, the names of the victims and their dates of birth and death are projected onto the four walls, while a low voice reads their brief biographies. It takes nearly seven years of uninterrupted reading to honor the memory of the victims of the extermination.

Continuing north along Karl-Liebknecht-Str and Ebertstrasse, you will arrive at the moving Monument to the Victims of the Wall, erected in memory of those who died trying to escape from the DDR. Just a few steps from the monument stands the imposing Reichstag, the seat of the German parliament.

The Reichstag became the seat of the Bundestag, the German Parliament, in 1999 when the restoration overseen by Lord Norman Foster was completed. The renowned English architect transformed the 1894 building, designed by Paul Wallot, into a state-of-the-art complex, preserving only the original external structure and adding extraordinary contemporary elements, such as the sparkling glass dome. The rapid elevator ascent to the top is a must for anyone visiting Berlin, offering a 360° panorama of the city and stunning close-up views of the dome and the mirrored funneled center. The elevator delivers visitors to a panoramic terrace where there is also an expensive restaurant. From here, you can ascend a spiral staircase inside the dome itself, located right above the Plenary Hall. At the top, there are also explanations about the building’s history.

The Reichstag has been at the center of numerous crucial events in German history. After World War I, Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed the republic from one of its windows. The Reichstag fire on February 27, 1933, allowed Hitler to blame the Communists and seize power. A dozen years later, the victorious Soviet army nearly destroyed the building. Restoration, except for the dome, was not completed until 1972. On October 2, 1990, at midnight, the reunification of Germany was proclaimed from here. In the summer of 1995, the Reichstag once again made headlines worldwide when Christo (the famous Bulgarian artist known for ‘wrapping’ public monuments) and his wife Jeanne-Claude wrapped the building in plastic sheets. Lord Norman got to work shortly after.

As you continue on, prepare your camera to capture the majestic Brandenburg Gate, the ultimate symbol of German reunification. The famous Brandenburg Gate, recently restored and a symbol of the division between the two Berlins during the Cold War, now stands as a guardian of embassies, an icon of reunified Germany. It was here, in front of this gate, that in 1987 the then-President of the United States, Ronald Reagan, uttered the now-famous words: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” Two years later, the Wall would become a thing of the past. The structure, designed by Carl Gotthard Langhans in 1791, is the only gate that has survived out of the 18 city gates. The Quadriga by Johann Gottfried Schadow, the sculpture of the winged goddess of victory guiding a horse-drawn chariot, proudly stands atop a backdrop of Doric columns. Napoleon seized the sculpture in 1806 and kept it in Paris for years. However, with Napoleon’s defeat, the winged goddess was liberated from a gallant prussian general.

The gate leads to Pariser Platz, a harmoniously proportioned square where you could visit the DZ Bank and ask for permission to take a look at the stunning atrium designed by Frank Gehry.

From here you reach Unterden Lunden, Berlin’s historic grand boulevard. As you walk east, you’ll soon spot, on your right, the Russian Embassy, housed in a monumental white marble building. Nearby, you’ll find the elegant Café Einstein, perfect for a refined break. Turning right at Friedrichstrasse, you’ll reach the luxurious Friedrichstadt area. Inside the Galeries Lafayette, designed by architect Jean Nouvel, you can admire the striking glass cone. Remarkable also are the marble decorations by Fienry Cobb and I.M. Pei in Quartier 206. The dining options in Quartier 205 offer various ways to satisfy your hunger.

Just 500 meters from here, you’ll find Checkpoint Charlie, the most famous border crossing between East and West Berlin throughout the Cold War.

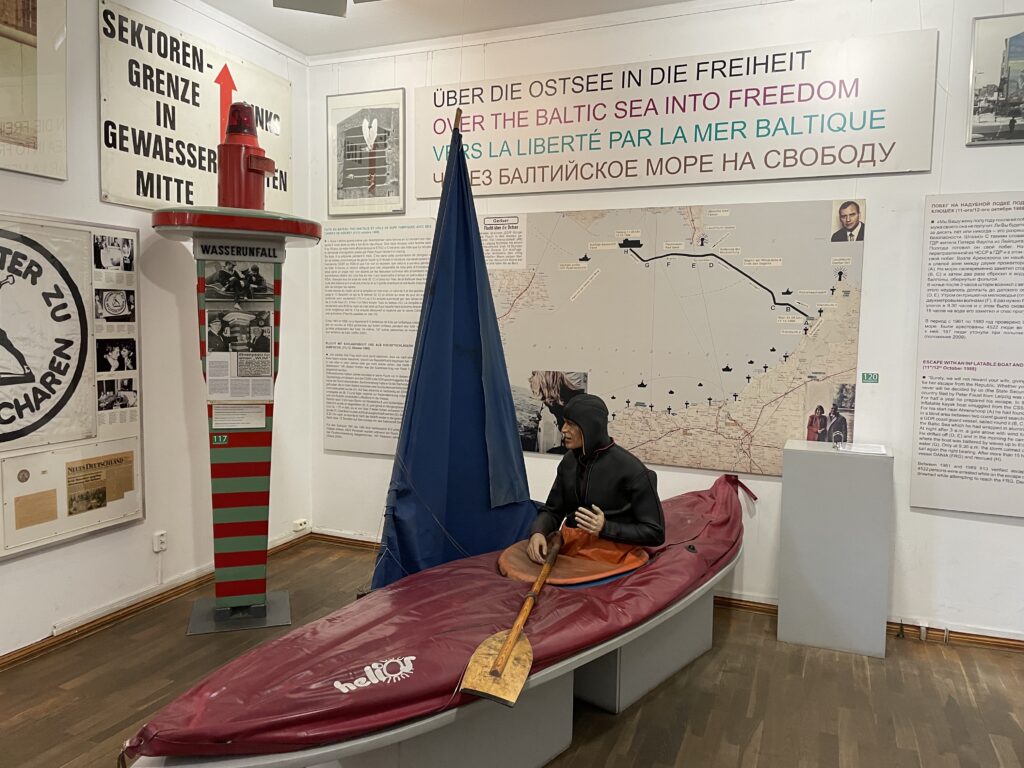

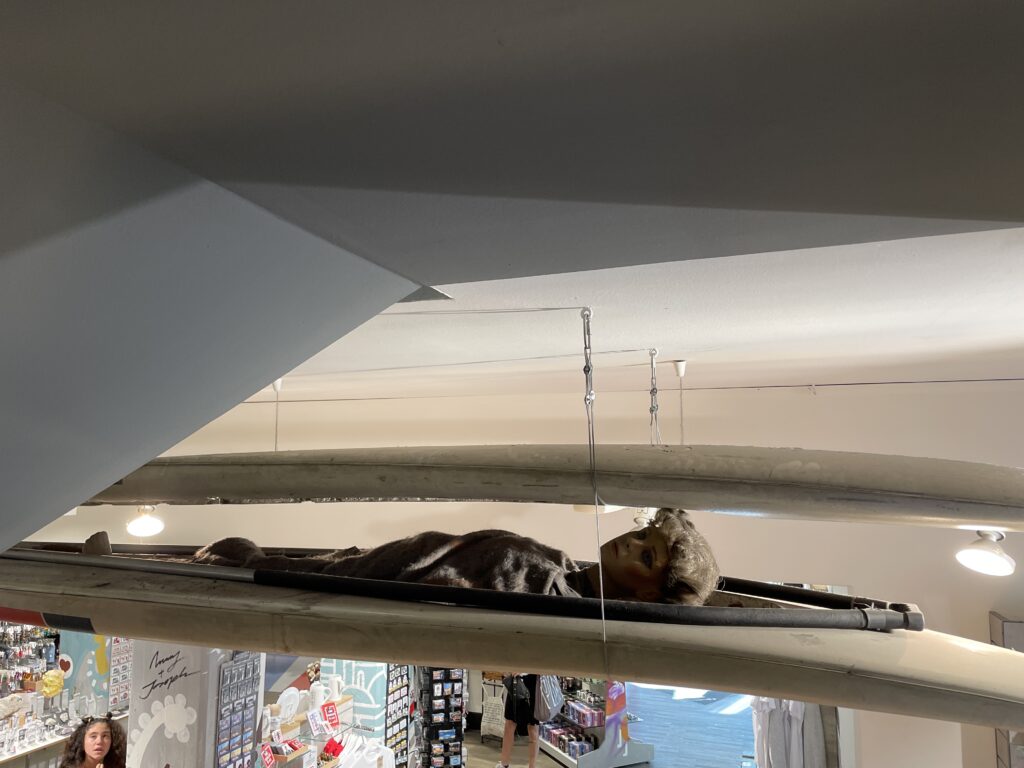

Alpha, Bravo, Charlie… The American phonetic alphabet inspired the name of the third Allied checkpoint in post-World War II Berlin. A symbol of the Cold War, Checkpoint Charlie was the primary crossing point for Allies, diplomats, and other foreigners who were permitted to travel between the two Berlins from 1961 to 1990. It was here that American and Soviet tanks faced off in October 1961, bringing the world to the brink of a third world war. To commemorate this historic site, Checkpoint Charlie has been partially reconstructed. There’s a guardhouse from the American military (the original is at the Allierten Museum,) and a replica of the famous sign that warned ‘You are leaving the American sector’ in English, Russian, French, and German. The original sign is now located immediately next door, in the Haus am Checkpoint Charlie Museum. A new office district – with buildings designed by Philip Johnson and other international architects – has arisen around what was once a restricted area.

In the nearby Haus am Checkpoint Charlie you’ll find a captivating account of the years of the Cold War, with a strong emphasis on the history and horrors related to the Berlin Wall. Moving is the section that narrates the courage and ingenuity of some citizens of East Germany who attempted to escape to the West using hot air balloons, tunnels, hidden car compartments, and even a submarine with a single crew member. The rest of the museum focuses on the historical events that marked the city’s life, including the Berlin Airlift, the 1953 workers’ uprising in East Berlin, the construction of the Wall, and the reunification. There is also an original section of the white line that marked the border, where American and Soviet tanks faced off at Checkpoint Charlie in 1961. Other rooms are dedicated to human rights heroes (Gandhi, Lech Walesa, and others) and the world’s major religions. Explanatory panels are in various languages, and the museum also features a café and a shop.

If you’re not interested in the Wall’s history, you can continue your journey directly from Quartier 205 by turning left onto Mohrenstrasse, which will lead you to Gendarmenmarkt, Berlin’s most beautiful square, featuring the Konzerthaus designed by Schinkel and the towering Deutscher Dom and Französischer Dom cathedrals.

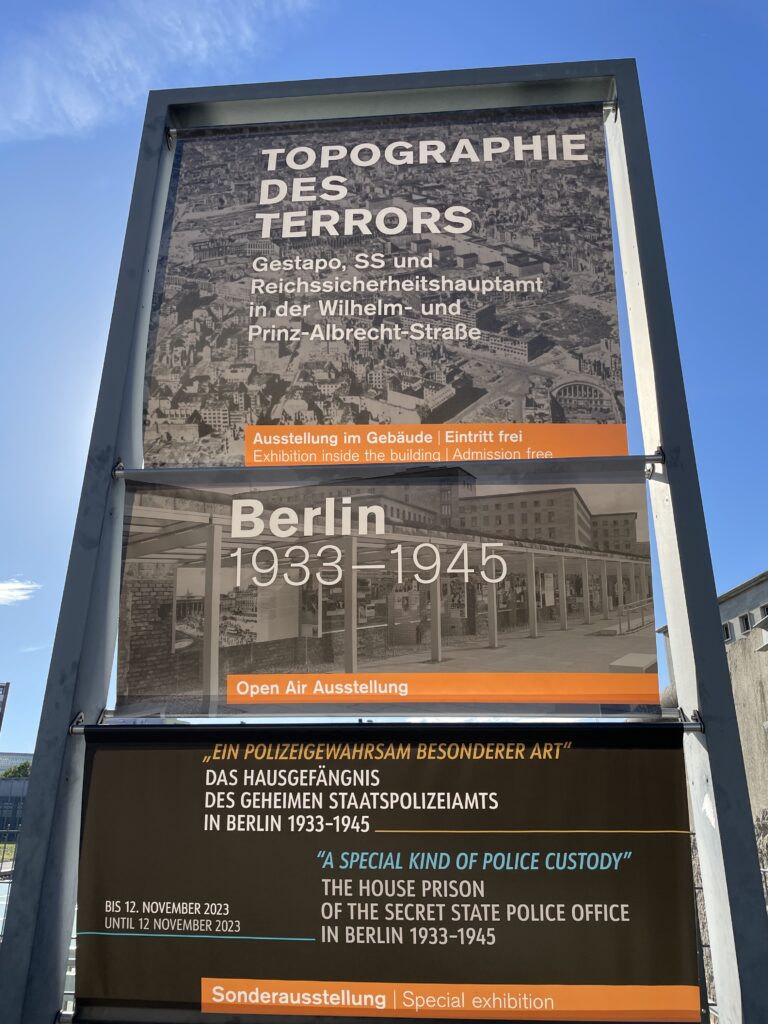

Finish your walk in the abandoned area along Niederkirchner Strasse, the most feared institutions of the Third Reich once stood: the Gestapo headquarters, the central command of the SS, the SS security service, and, after 1939, the central office of Reich security. From their desks, Nazi leaders planned the Holocaust and issued arrest warrants for political opponents, many of whom were tortured and killed in the infamous Gestapo prison. Today, the buildings have been demolished (there are signs indicating their layout), and a eerie atmosphere lingers over the abandoned grounds, whose sinister appearance is accentuated by a short section of the Berlin Wall that still stands. Since 1997, this has been the site of a poignant outdoor exhibition called “Topographie des Terrors” (Topography of Terror), primarily dedicated to the years of the Third Reich, with a particular focus on the historical significance of this site and the brutal institutions that occupied it.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Day 2- Contemporary architecture

Berlin has always been a testing ground for avant-garde architects, but never more so than during the post-reunification building boom. The fall of the Wall made vast empty spaces available, offering the city an opportunity to reshape its image in stone, steel, and glass. The itinerary that follows covers three main areas: the government district, the diplomatic quarter, and Potsdamer Platz.

Start at the Reichstag, the historic seat of the German parliament and the heart of the new Band des Bundes (federal ribbon), as the new urban complex of ministerial and parliamentary buildings is called.

To the north of the Reichstag, turn right onto Paul-Löbe-Allee, pass by the ultramodern Paul-Löbe-Haus (p104), and continue to the Spree River. Following the riverside promenade northward, you’ll spot the futuristic Marie-Elisabeth-Lüders-Haus on the opposite bank. If you want to get a closer look at the building, you can cross the pedestrian bridge, or you can turn west, first skirting the north side of the Paul-Löbe-Haus and later the Swiss Embassy, which has added a postmodern wing to its historic headquarters.

In the meantime, though, your gaze will likely be drawn to the enormous Bundeskanzleramt (Federal Chancellery), where the Chancellor holds cabinet meetings. Heading south on John-Foster-Dulles-Allee, you’ll pass the Haus der Kulturen der Welt.

The extravagant House of World Cultures (Haus der Kulturen der Welt) by Hugh Stubbins represented the American contribution to the 1957 Interbau, an architecture exhibition that brought together the most esteemed international talents in Berlin. Originally designed as a congress hall, its most distinctive design element is the parabolic roof that defies gravity and covers the building like a gigantic shell. Berliners affectionately nicknamed it the ‘pregnant oyster.’ Unfortunately, the architect’s vision was too ahead of its time compared to the technological means available at the time, and the roof partially collapsed in 1980. After reconstruction in 1989, the complex became a cultural center with a rich program of art exhibitions, conferences, seminars, concerts, and other world-class events.

The pond reflects the lines of Henry Moore’s sculpture “Divided Oval: Butterfly,” whose curved profile echoes the building’s design. The 68 bells of the marble and bronze carillon – the largest in Europe – chime at 12 and 18 o’clock every day. On Sundays at 3 o’clock from May to September, a carillonneur performs live concerts, followed by guided tours of the tower.

Continuing west, look across the Spree to where a new residential mega-complex for government employees called Die Schlange, the snake, due to its undulating shape, is taking shape.

Turning left onto Spreeweg, you’ll pass Schloss Bellevue, the presidential residence. This neoclassical white stucco palace, recently renovated, is located on the northwestern edge of Tiergarten and serves as the official residence of the President of the Republic (at the time of writing this guide, Horst Köhler held the position). It was built in 1785 by Philipp Daniel Boumann for the younger brother of Frederick the Great, then later became a school under Emperor Wilhelm II and an ethnology museum during the Nazi era. The President and their staff have their offices in the Bundespräsidialamt building from 1998, just south of the palace. This essentially is the German version of the ‘Oval Office’ of the American White House, referring in this case to the elliptical shape of the entire building, covered in glass and polished black granite. Architecture enthusiasts might want to take a look at a wavy residential complex that stretches 300 meters called “Die Schlange” (the snake), located northeast of the palace on the other side of the Spree River.

Dominating the landscape is the Siegessäule (Victory Column), a triumphal column commemorating Prussian military victories in the 19th century, particularly against Denmark (1864), Austria (1866), and France (1871). The large golden lady on top (standing at a height of 8.3 meters) represents the goddess of Victory, although locals simply refer to her as ‘Golden Elsa.’ Film enthusiasts may remember her in the iconic scene from Wim Wenders’ 1987 film “Wings of Desire” (Himmel über Berlin). The Nazis relocated it here from its previous location in front of the Reichstag in 1938 and added an extra tier to the column, making it an impressive 67 meters tall. You can climb to the top of the column; admission tickets also allow you to visit the small museum and enjoy discounts at the adjacent café and Biergarten. The Siegessäule has become a symbol of Berlin’s gay community (the city’s most prominent gay publication is named after it) and marks the endpoint of the annual Christopher Street Parade. The park around the column is a popular gathering spot for the LGBTQ+ community, especially around the Löwenbrücke area.

Then proceed along Hofjägerallee.

Before long, you’ll see the turquoise façade of the Nordic Embassies (p55) on the other side of the Spree. The complex is very striking at night when it appears as a giant illuminated crystal. Next to it is the equally remarkable Mexican Embassy (p55), preceded by a row of inclined concrete columns. Following the new main quarter of the CDU, one of Germany’s main political parties. The extravagant building resembles a transatlantic liner enclosed in an anvil-shaped glass shell.

On the opposite side of the street is the Bauhaus Archiv, designed by the godfather of modern architecture, Walter Gropius. It’s worth taking a look inside the museum and perhaps stopping for a drink in its café before continuing east along Von-der-Heydt-Strasse and then turning north onto Hiroshimastrasse.

This street features the beige building of the Japanese Embassy M (p51) and the pink one of the Italian Embassy 1 (p50). Both date back to the Nazi era, which explains their pompous style and large size. Continuing east along Tiergartenstrasse, you’ll pass the new South African Embassy V at No. 18, and then turning onto Stauffenbergstrasse, you’ll see the Austrian Embassy (p55). Immediately south of this is the Egyptian Embassy 9 (p55), easily recognizable by the inscriptions decorating its reddish-brown façade.

Further on, the diplomatic quarter gives way to the Kulturforum 20, an architectural showcase created between 1961 and 1987. The most eye-catching building here, especially due to its unique roof, is the Philharmonie 2, completed in 1963 by Hans Scharoun.

From here, our itinerary continues towards Potsdamer Platz, a true treasure trove of contemporary architecture. Arriving from Bellevuestrasse, you’ll see the Beisheim Center 0D on your left, a building inspired by American skyscrapers from the 1950s. To your right, you’ll spot the Sony Center (p108) with its spectacular covered square and the soaring glass skyscraper of the talented Helmut Jahn. South of Potsdamer Strasse stands the Daimlercity Complex (p107), an expression of the creative talent of various architects from around the world. RafaelMonser Bulato c (so-called io (49363), Renzo Piano’s design for the Daimlerchester Building © (p1OTe deritalporaente, and Kolhoff & Kolhoff Haus @, with its distinctive Volksbank & i brickwork, are worth a visit. If you’re in need of a refreshment, you’ll have plenty of restaurants and cafes to choose from in Potsdamer Platz.

South of Potsdamer Strasse stands the Daimlercity Complex (p107), an expression of the creative talent of various architects from around the world. RafaelMonser Bulato c (so-called io (49363), Renzo Piano’s design for the Daimlerchester Building © (p1OTe deritalporaente, and Kolhoff & Kolhoff Haus @, with its distinctive Volksbank & i brickwork, are worth a visit. If you’re in need of a refreshment, you’ll have plenty of restaurants and cafes to choose from in Potsdamer Platz.

Day 3 - Hamburger Bahnhof

The smiling Mao by Andy Warhol, the luminous abstractions of Cy Twombly, and the provocative installations by Joseph Beuys are part of the collection of Berlin’s most important contemporary art museum, which picks up where the Neue Nationalgalerie (p111) leaves off (around 1950). Beuys enthusiasts will be satisfied, as the entire western wing is dedicated to the enfant terrible of late 20th-century German art. The other exhibitions change periodically, but you’ll probably be able to admire works by Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, Keith Haring, Duane Hanson, and Cindy Sherman. Just as interesting as the artworks contained here (according to some, even more so) is the architecture of the building, a late Neoclassical-era former train station transformed by Josef Paul Kleihues. The main atrium, a spacious area adorned with iron structures, is the perfect setting for large paintings, installations, and sculptures: Richard Long’s Berlin Circle, Mario Merz’s igloo, Anselm Kiefer’s Blei Bibliothek (iron library). The sparkling white façade exudes great elegance and grandeur, especially at night when a luminous installation by the late Dan Flavin bathes the building in kaleidoscopic shades of blue and green. In 2004, the museum spaces were expanded into the adjacent Rieckhallen, a series of interconnected industrial structures previously used by a transport company. Set within corrugated metal panels resembling a giant container, they house works from the prestigious collection of Friedrich Christian Flick, a German industrialist with a passion for modern and contemporary art. The exhibitions change periodically but often include masterpieces by prominent contemporary artists such as Bruce Naumann, Paul McCarthy, Rodney Graham, and Jason Rhoades, along with notable figures from early 20th-century art, including Sol LeWitt, Marcel Duchamp, Nam June Paik, and Sigmar Polke. The museum lives up to its title of “Museum für Gegenwart” (museum of the present) by also presenting a packed calendar of concerts, readings, films, and meetings with artists.

Day 4-

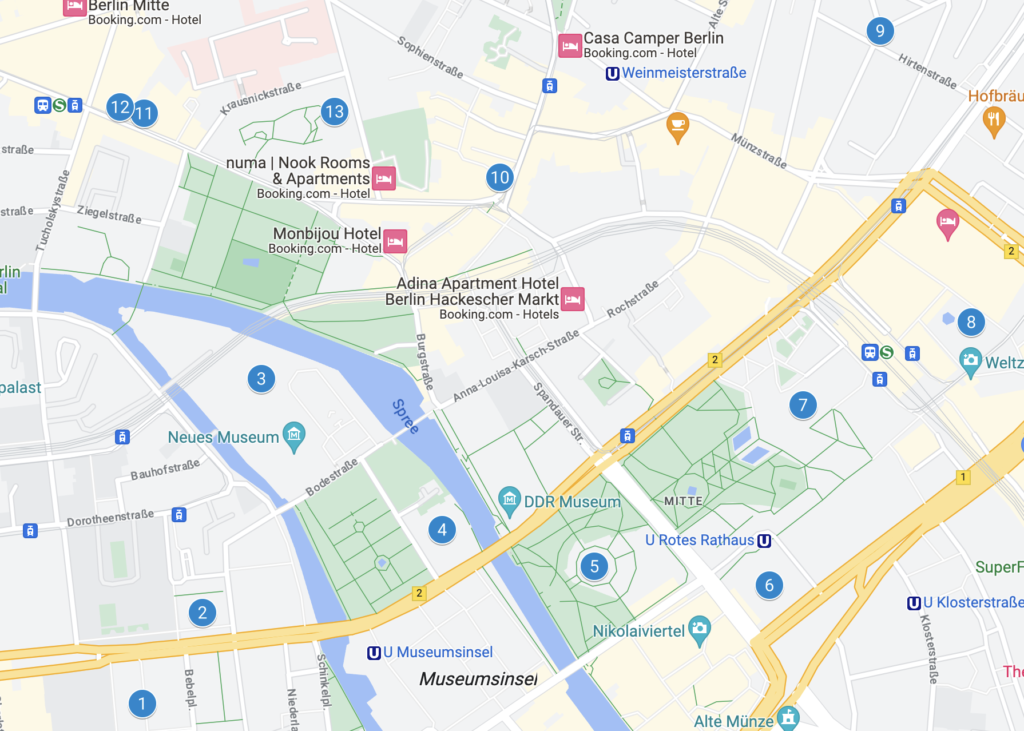

Start your walk from Bebelplatz. This square is named after August Bebel, co-founder of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), and is primarily known because the Nazis organized their first official book burning here on May 10, 1933. During this event, the works of authors considered subversive, including Bertolt Brecht, Thomas Mann, Karl Marx, and others, were set ablaze. It was a terrifying event that marked the end of the cultural greatness that Berlin had acquired in the preceding two centuries. A moving memorial to Micha Ullmann, consisting of an underground library with empty shelves, keeps the memory of this tragic event alive.

Bebelplatz was conceived as the focal point of the Forum Fridericianum, Frederick the Great’s project to create an intellectual and artistic center inspired by ancient Rome. Unfortunately, the king’s costly military ventures depleted the state’s coffers and made it impossible to complete such a grand endeavor.

Nevertheless, several of the planned buildings were constructed, including the Alte Königliche Bibliothek on the western side of the square, and across from it, the Staatsoper Unter den Linden and the Sankt-Hedwigs-Kathedrale in the southeast corner. Next to the church stands the new Grand Hotel de Rome, a temple of luxury hospitality in a prestigious location, housed in a building from that was previously occupied by the state bank of the GDR. The hotel is part of a building development project called Operncarré, which also includes residences, offices, and shops. Along Bebelplatz, Unter den Linden also runs, which at this point is flanked by beautiful historical buildings, including Humboldt University and the Neue Wache by Schinkel. Built in 1818, the neoclassical Neue Wache (New Guardhouse) was Schinkel’s first significant commission in Berlin and is now a monument in memory of ‘the victims of war and tyranny.’ Inspired by a classical Roman fortress, it features a double row of columns supporting a pediment adorned with allegorical war scenes, giving it a certain authority. The original inner courtyard was covered in 1931, and the shaft of light that penetrates it strikes the moving sculpture by Käthe Kollwitz, “Mutter mit totem Sohn” (Mother with Dead Son), also known as Pietà. Beneath the austere hall lie the remains of an unknown soldier, a resistance fighter, and soil from nine European theaters of war and concentration camps.

Take a look at the Reiterdenkmal Friedrich des Grossen (statue of Frederick the Great), a western sculpture by Christian Daniel Rauch. The elaborate building you can see a little further ahead on the south side of Unter Den Linden is the Kronprinzenpalais, the former residence of the crown princes, while the pink palace opposite it is the Zeughaus, the old arsenal that now houses the Deutsches Historisches Museum (German Historical Museum). It’s also worth taking a look at the new wing designed by I.M. Pei. Continue to Bodestrasse, then turn east and cross the bridge leading to the Museumsinsel, an exceptional complex of museums with a rich heritage of painting and sculpture.

If you have limited time and need to visit only one of the museums in Berlin, undoubtedly choose the Pergamon Museum. It is a true triumph of classical Greek, Babylonian, Roman, Islamic, and Middle Eastern art and architecture, originating from excavations conducted by German archaeologists in the early 20th century. This gigantic complex, which was only completed in 1930, actually houses three significant collections under the same roof: the Collection of Classical Antiquities, the Museum of the Ancient Near East, and the Museum of Islamic Art. Each one is worth visiting at a leisurely pace, but if you have limited time, focus on the following highlights.

The main artifact from which the museum takes its name is the reconstruction of the Pergamon Altar (165 BC) from Asia Minor (in Bergama, modern-day Turkey). It is a colossal sanctuary dedicated to Zeus, with a staircase leading to a U-shaped colonnade. Incredibly vivid friezes depicting episodes of the Gigantomachy, the battle of the gods against the giants, are carved along the entire base. Ascend the steps of the altar to closely admire the Telephus frieze, which narrates the myth of the founder of Pergamon, the son of Heracles.

The next hall contains another important artifact: the immense Market Gate of Miletus (1st century AD), a masterpiece of Roman architecture. The Museum of Ancient Middle Eastern Antiquities presents a completely different culture: that of Babylon during the time of King Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 BC).

It is impossible not to feel awe in front of the reconstructions of the Ishtar Gate, the ‘processional way’ leading to the gate, and the façade of the throne room. They are all adorned with bricks painted in cobalt blue and ochre. The rampant lions, horses, and dragons representing the main deities of the Babylonians are so impressive that you can almost hear their roar and the fanfare. Another wonder in the collection is the intricate façades of the Temple of Uruk, decorated with colored clay inserts and highly detailed bas-reliefs. Finally, in the Museum of Islamic Art, don’t miss the palace of the caliph of Mshatta from the 8th century in present-day Jordan, resembling a fortress. Also, highly visited is the Aleppo Room from the 17th century, originating from a Syrian merchant’s house, where the walls are entirely covered with painted and richly decorated wooden panels. Try to allocate at least two hours to this incredible museum.

Dominating the island is the silhouette of the magnificent Berliner Dom, where many members of the Hohenzollern dynasty are buried; the cathedral’s gallery offers a splendid panoramic view of the city. Overlooking the cathedral stood the now-demolished Palast der Repubik, demolished in 2007 by the DDR government. They plan to build a replica of the royal palace that originally stood in its place.

After passing the cathedral, turn right and reach the Mark-Engels Forum, alongside statues of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and continue to the nearby Rotes Rathaus (Red City Hall), the seat of the municipal administration

Continue eastward, and if you have time, ascend the Fernsehturm (Television Tower), the tallest building in Berlin, soars to 368 meters towards the sky. From the panoramic platform, located at a dizzying height of 203 meters, you can distinguish the city’s main monuments and points of interest, admire the size of Tiergarten Park, and compare the urban layout of what used to be East and West Berlin. At the top, you’ll find the Telecafé, which serves coffee, snacks, and full meals while completing a full 360° rotation in 30 minutes. Built in 1969, the tower was supposed to showcase the technological superiority of East Germany (DDR), but instead became a source of embarrassment. When illuminated by the sun, the steel sphere beneath the antenna produces a reflection resembling a giant cross – certainly not a welcomed sight in an atheist country where crosses were even removed from church rooftops. Western Berliners wittily nicknamed the phenomenon ‘the Pope’s revenge.’

Head then to Alexanderplatz. Once the hub of commercial activities in East Berlin, Alexanderplatz – often abbreviated as “Alex” – was originally called Ochsenmarkt (Oxen Market), but it later changed its name in honor of Tsar Alexander I, who visited Berlin in 1805. Today, it’s just a shadow of the vibrant neighborhood that Alfred Döblin described as the pulsating heart of a cosmopolitan city in his 1929 novel, “Berlin Alexanderplatz.” Severely damaged during the bombings of World War II, it acquired its current appearance, strictly adhering to socialist principles, in the 1960s thanks to the urban planners of the German Democratic Republic (DDR). The Fernsehturm (TV Tower), the Interhotel Stadt Berlin standing at 123 meters, and the Centrum Warenhaus (now Kaufhof), which was once the DDR’s most important department store, all date back to that era.

Among other famous landmarks are the Brunnen der Völkerfreundschaft (Fountain of Friendship among Peoples) and the Weltzeituhr (World Time Clock). Adjacent to these is the Haus des Lehrers (House of the Teacher) with a frieze by Walter Womacka, which is now part of the nearby Hig Berlin Congress Centre.

Although there are plans to transform Alexanderplatz into a mini-Manhattan dotted with skyscrapers, the program (for now) remains on hold due to a lack of funds and investments. Nevertheless, the square is gradually changing its appearance. In 2005/06, the Kaufhof department store underwent a complete overhaul according to the design of Josef Paul Kleihues. The traditional honeycomb façade was replaced with a sleek glass and travertine covering, along with the addition of a bright central courtyard with a glass dome.

Not far away, the 1929 Berolinahaus by Peter Behrens is being transformed into a branch of the C&A clothing store chain, which opened its first store in Alexanderplatz in 1911. And not too distant, in an area bounded by Alexanderstrasse, Dircksenstrasse, and Grunerstrasse, the new Alexa Shopping Mall is taking shape. The Franco-Portuguese investors hope to be active there by early 2007 with approximately 200 shops and a large fitness center, as well as dining options.

Leave the square and proceed along Münzstrasse, a street leading to Scheunenviertel, the historic Jewish quarter of Berlin, now one of the liveliest areas in the city, filled with excellent restaurants, shops, and nightspots. Turn left at the intersection with Neue Schönhauser Strasse, a street brimming with boutiques and shops offering the most original creations, and then turn left again on Rosenthaler Strasse, arriving at the Hackesche Höfe, a series of beautifully restored interconnected courtyards filled with bars, shops, and entertainment venue. One of the most well-known tourist attractions in Berlin, the Hackesche Höfe (1907), is a complex of eight beautifully restored courtyards filled with cafes, art galleries, fashionable boutiques, and entertainment venues. The most charming is Hof I (entrance from Rosen-thaler Strasse), whose facades are adorned with rich Art Nouveau tiles designed by the artist August Endell. From Hof VII, you can access the Rosenhöfe, a small single courtyard with a rose garden lower than street level. The metal balustrades with intricate flower and branch motifs create a quirky ensemble.

Take Oranienburger Strasse, the main street of Scheunenviertel, and head north, perhaps taking a break by the river at Monbijoupark. Soon, you’ll reach the beautiful Neue Synagogue (New Synagogue), the most prominent symbol of the rebirth of the Berlin Jewish community.

The glittering golden dome of the New Synagogue stands as a symbol of the revived Jewish community in Berlin. Designed in Moorish-Byzantine style by Eduard Knob-Rauch, the original synagogue from 1866 could seat 3,200 people and was the largest synagogue in all of Germany. Thanks to its beauty and rich decorations, it became an important city monument. During the 1938 pogrom, known as Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass), a local police superintendent prevented the SS from setting fire to the building, an act of courage commemorated with a plaque. Nevertheless, the Nazis managed to desecrate it, although religious services continued until 1940 when the synagogue was expropriated and turned into a warehouse. Allied bombs nearly destroyed the building in 1943. With the consent of the small East Berlin Jewish community, the East German government demolished much of the ruins in 1958, leaving the main facade as a memorial. In 1988, Honecker announced his government’s decision to rebuild the synagogue, but the regime collapsed before the project could begin. The reunited German government adopted the project, and the New Synagogue was inaugurated in May 1995. It serves not only as a place of worship (though religious services are held in a small room on the second floor) but also as a museum and information center. Permanent exhibitions document the history and architecture of the building and its role in the lives of those who practiced their faith there. Among the items on display are a model of the synagogue, a Torah scroll, and a perpetual lamp from the original structure, unearthed during excavations in 1989.

Guided tours take you behind the building, where a glass and steel structure supports the remaining ruins of the sanctuary, and a stone band outlines the giant profile of the original synagogue. There is also a dedicated space for special exhibitions on the upper floor. The dome is accessible from April to September.

Adjacent to the synagogue is the entrance to the Hackmanhöfe, another creatively restored courtyard complex.